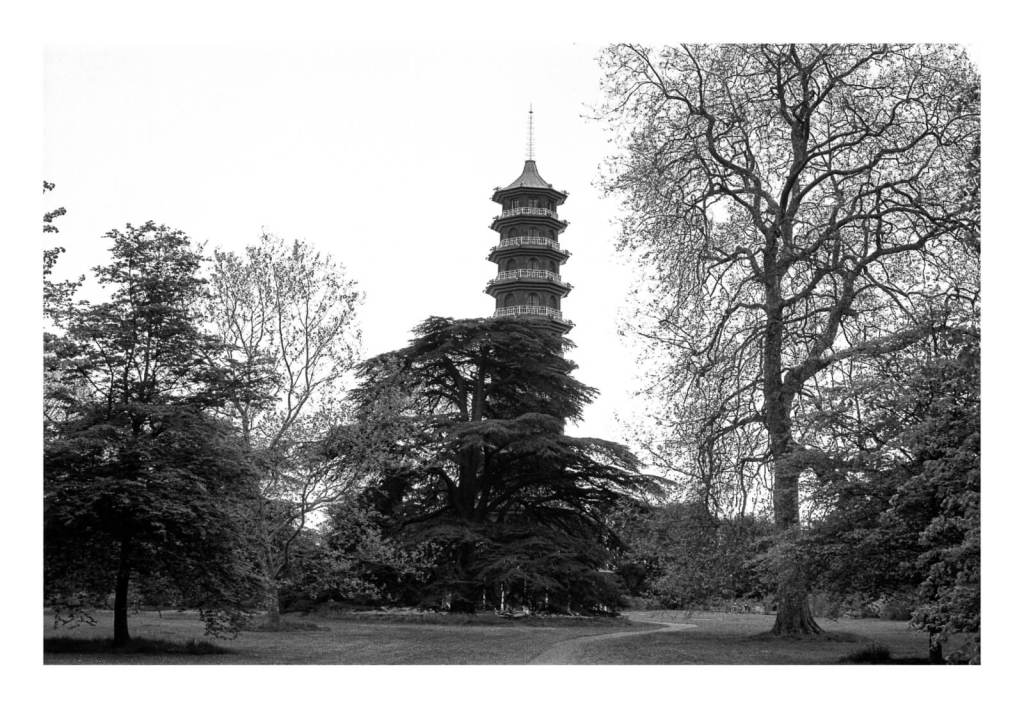

It was the hottest day of the year, and I spent it in the garden. I climbed the Great Pagoda. The pagoda was made of a carefully decorated outer shell, a spiralling staircase set in the middle of wooden floors, and an emptiness divided into ten storeys. Its interior had the feeling of being left unfinished; it was hard to tell if this was intentional. The lack of objects made the inside of the pagoda seem brighter than the garden outside the window. Sunlight was accumulating here, filling this void until it assumed the shape of a tower too. The pagoda was a mould for light. I stood on the top level with sweat dripping from my hair. There wasn’t even a breeze. And all the while I kept thinking: my grandfather had died. It had only been a few days, and there I was, visiting a pagoda in a garden thousands of miles away from home. How could two completely unrelated things have happened to me, so close in time, yet so far apart in space?

Each floor of the Great Pagoda had a hole, now sealed with plain glass. Standing next to the one on the highest level, you could look down and see all the other holes underneath it. Or rather, you could see the absence of the floor sections. They had been cut out during the Second World War, when the pagoda was used as a test site for smoke curtain installations. Scientists would fire smoke down through these holes, monitoring how its density was affected by changes in pressure and the chemical mixture. Back then, instead of light, this place was a mould for smoke. Here was the hint of a gesture: of cutting out, neatly, a calculated area on a thin, flat surface; of lining up one hole with another until a clear pathway emerged, allowing air to travel all the way to the end, as if life depended on it. But yes, life did depend on it, on the precise ratio of air versus smoke and the artificial pathway constructed at a formerly enclosed space, and these two, together, made breathing possible. It was a paradox. Those tests were suffocating the pagoda, and they were what enabled it to breathe.

So it was that, when I walked into the Great Pagoda and saw that row of holes, now useless but left there, sealed, yet not concealed, I thought of my grandfather who had died, who had received a tracheostomy shortly before his death. Rather than him, I thought of that desperate procedure, of the small, precise incision that had been made on the front of his neck and windpipe, and the tracheal tube inserted. By then he had stopped being able to breathe on his own. Later my mother had told me about blood. There was blood, she said, I was scared, but at least he could breathe. The pagoda was so clean. Its clean floor and clean, light-coloured walls, the spotless railing of its staircase and those spotless glasses that must have been wiped on a regular basis—who would do such a thing? For what? The neat materiality all around me served as a reminder of the messy materiality of a failing, failed, body, another site that, despite numerous tests and operations, could no longer fulfil its functions in the end. I stood there for so long that what I saw turned into a reminder that such a cut had really happened to him, and everything before my eyes contained a testimony. And then, the act of entering this void became walking into his throat.

Let me try this again.

The Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens has a total of ten storeys. A Chinese pagoda might have five, seven, nine, thirteen, fifteen storeys, and so on and so forth—always odd numbers, never even numbers. The floor plan of each storey might be a rectangle, a hexagon, an octagon, and so on and so forth—always even numbers, never odd numbers. The architect of the Great Pagoda got it wrong, unless, of course, the supposed correctness of the design doesn’t matter all that much. It is an example of chinoiserie, not of a precise replica. It is a tourist attraction with no actual religious function, inside a botanical garden. I doubt that Sir William Chambers had anyone like me in his mind when he was drawing up his initial sketch. It was more than likely that when he thought of tourists he was thinking of a very specific group of people, one that undoubtedly excluded me. It was by pure chance that, looking to distract myself from grief, I encountered the pagoda, with its site, shape, and history that, instead, situated me in relation to my home-bound grief.

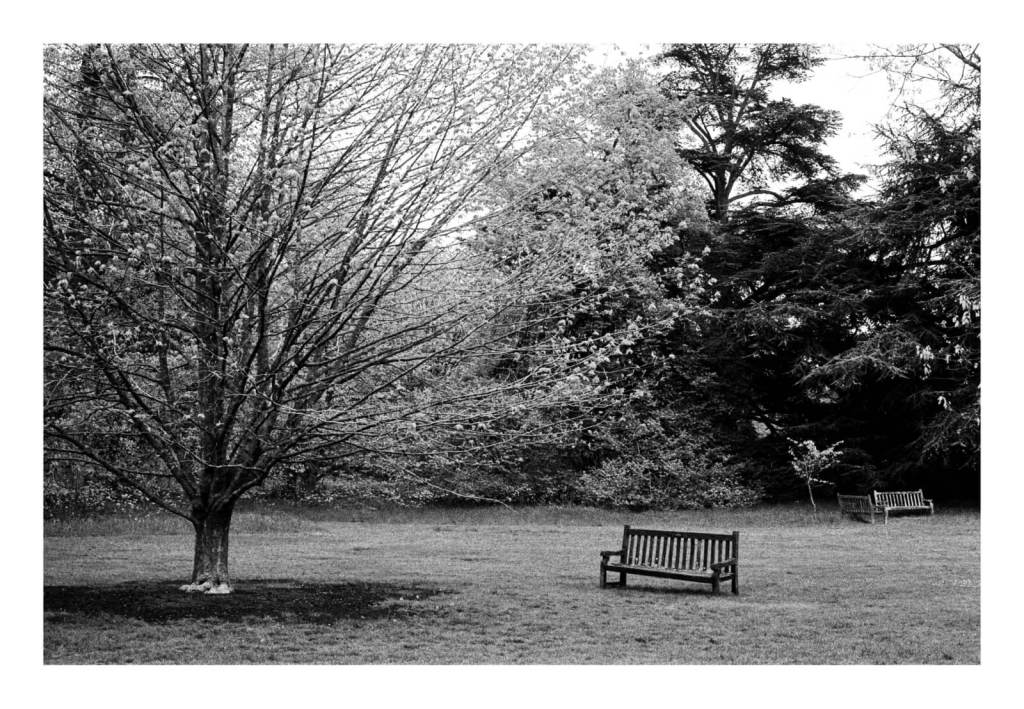

It was not only that those holes on the floor connected the body of the pagoda to that of my grandfather. It was not only that its failure to pass as an authentic piece of Chinese architecture mirrored the failure of his body to hold onto life, no matter how closely it still mimicked that bodily condition called living, for a time after that specific life had ended, after he was pronounced dead. For a time his body retained its shape, in the exact way it had been familiar to us. How fast, or slow, does a person transform from being acceptably alive to thoroughly dead? But this is not what I meant to say. I meant to say—no, not only these, but also, the pagoda is a decoration, a toy, inside a garden, which is itself another kind of toy, on a much larger scale. I grew up close to such a garden. It was the only botanical garden in our city, within walking distance of my grandparents’ place. I grew up under the care of my grandparents, like many other Chinese kids around my age. My grandparents would take me to the botanical garden multiple times every week. We had picnics there, played ball on the lawn, drew trees and flowers, and for the most part just wandered around aimlessly. In that garden people worked to ensure that the four seasons manifest to the uttermost extent. In that garden I began to learn that every flower had its time, and then there was winter, which meant yellow grass and dead branches that were not truly dead, the sort of nothing that was never truly nothing. Except that everything there had been designed and planted; everything we saw, brought together by diligent cultivation I was too young to recognise and therefore took as the way nature was. In a botanical garden the line between the natural and the artificial gets blurred, especially if the garden expands into a rather deceiving scale. When I walked into Kew Gardens on that sweltering summer morning, what I entered was a carefully controlled ecosystem, and part of what was under control was material exchange. A visitor wouldn’t normally feel free to poach birds or squirrels, nor collect beetles or butterflies, nor break tree branches or flower stems to take them home. By the same token, they were not allowed to plant in the garden or set free animals that would then become intruders. Through the limitations set on such exchanges, order was maintained, meaning that here in this place, life and death were regulated. More regulated than a lot of other places, at least. If only the same kind of control could be applied to grief.

When someone dies, you stop being able to make exchanges with them. You can’t talk with them, eat with them, or just be with them, physically, in the same space. They are no longer there. They will never come back home. I don’t believe they will, because otherwise I should have already seen my grandfather by now, and this lack of chance encounter is proof enough for me that ghosts, in the commonly accepted sense of this word, do not exist. So he, or rather, his ashes, remain in that cemetery, inside a ceramic urn, underneath a tombstone. What is a cemetery if not a specimen room, the specimens being those tombstones, each one a sample of death and also its own label? Their heaviness and smoothness can’t help but come to stand for an absolute cutting off, between the dead and the living. They are steles marking out boundaries that forbid trespassing. What has been missed will never be made up for, and what has gone wrong, never corrected.

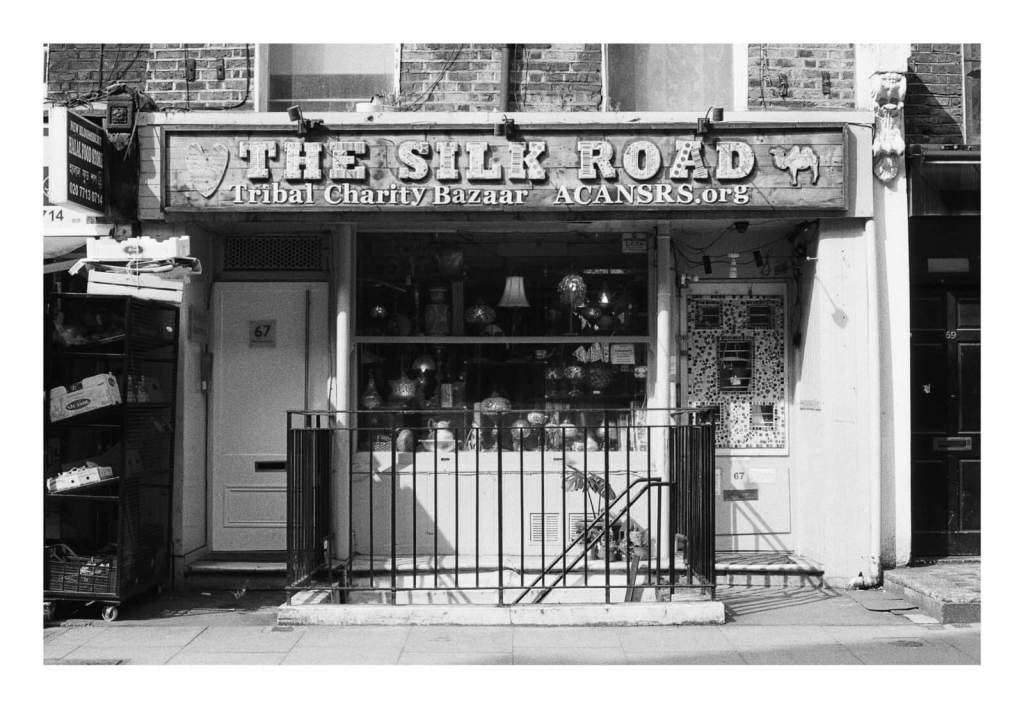

The very first time my mother had to travel for work, she was sent to Guangzhou. It was also the very first time she had ever worn high-heels. Back then, the trip required a ten-hour train ride from our city. She visited factories that manufactured marble tiles. It was summer, and the weather was very much like what I would later experience while climbing the Great Pagoda, in a different time and place, across continents. Except it was almost always humid and stifling in Guangzhou. It was so hot that the sweat on her soles made her shoes slippery. She stayed there for a couple of days, and because it was her first business trip, she wanted to bring home a gift. Right before she caught the train back, she bought a box of Hong Kong style egg tarts: six in total, for her parents, her younger brother and sister-in-law, her husband, and herself. It was just right. Plus, six was an auspicious number. Once she found her seat on the train she opened the box and saw the egg tarts placed neatly and very close to each other, six full circles, bright yellow, without even the tiniest dent on their smooth surfaces. Their smell was of a sweet that didn’t hint at anything else, sweet in a way that had the same fullness as their perfect shape. Simply by looking at them you would know that they were easy to break. They would go bad, grow mould, when you were not paying attention. And that was what happened, to my mother’s egg tarts. Not long after it started, the train went through mechanical failure, and broke down. Hundreds of passengers were trapped there, barely out of Guangzhou, inside the suffocating train, and they didn’t resume moving until more than half a day later. By the time my mother got home it was past midnight, and the dainty pastries had gone sour, every single one of them.

So you see, Ma, sometimes, or in fact for the most time, an accident that disrupts the original plan only occurs by chance, and the content of the accident is dictated by the shape this despicable chance happens to assume across time. It is not up to your determination, or even action, whether those precious egg tarts should rot onboard that long-distance train, or whether the already malfunctioning body of your father should stop functioning altogether. But then it is so easy to see this as one’s personal failure, for I feel the same way, though I never told you, Ma. Even today I sometimes believe that, if only we could have done one thing or another differently, he would have survived, or at least have lived longer. And then, it is against the backdrop of a place you call home that the intensity of every failure is measured. When William Chambers travelled, also to Guangzhou, on a ship that belonged to Swedish East India Company, he visited buildings and pagodas constructed by the locals in the authentic Chinese style; he put what he saw in his pocket and when he took it out on his familiar English shore, it had deformed, leaving him a vague resemblance of the original structure, a skeleton with the flesh half-eaten. So he had failed, in a sense, to preserve his memory and apply it to his design of the Great Pagoda. Only it didn’t matter, here at his home, whether the pagoda had ten floors or nine. Here it didn’t matter, since hardly anyone cared about the stylistic accuracy of a garden decoration. Because no one cared, or cares, it was, is, as if the failure has no weight at all. This weightlessness is what allows the pagoda not to present itself as a site of haunting. Those display cases on the ground floor, inside which sit model sailing ships peopled by crew figures, some positioned on deck and others along masts and sails, are for visitors to admire and play with, pushing buttons to see the ship flags wave. They are as innocent as the rest of the botanical garden: toys within a toy, again. Meanwhile there’s the kind of failure, albeit self-presumed, that haunts you wherever you go. To move closer to one’s home, or ruins of a place once known as home, is to sense the increasing magnitude of that failure, of irreversible loss. Since the death of my grandfather we have not returned to the botanical garden in our city. It would have provoked questions we could not answer. Yet walking into Kew Gardens and then into the pagoda I felt like a ghost. Or maybe the garden was a ghost, the pagoda ghost of ghosts, surrounded by trees I could or could not name. Yes, a ghost, for in this specific case what signals the existence of a ghost is deformity, that slight something you just know is off: a tower that largely resembles a shape you used to see every day but somehow has an extra floor, or the floors that appear intact but upon closer examination are all cut through and bearing those incurable holes. This uncanny act of entering a place you’ve never been to and finding it familiar, yet not quite right, mirrors the uncanniness of returning to a familiar place and finding it altered, strange, foreign, almost unrecognisable. They mirror each other in the sense that they exist in two separate realms and could not touch, could not be brought together and conjoined into one, and you get the feeling that if one of them is real, the other has to be a mere illusion, because that is how looking at yourself in the mirror is, it is the simplest and most persistent, most mundane form of haunting, because every time you look that image is there and it is not real, not of substance, and haunting is just that imbalance, that toppling over of an ordinary means of measure, a temporary disruption that dictates the way time flows during its occurrence, between you and a distorted mirror image that hollows out your language, for you could put the latter into words but what you are describing is, in the end, no more than a lack, the thorough absence of yourself, for the plain reason that you can’t cross the mirror and make that illusion corporeal. When I walked into the garden I became my mother’s ghost entering that other garden she could no longer bear to enter, and the garden around me became that garden’s ghost. And home, home was neither this or that, but the mirror which made haunting possible.

Let me try this yet again.

In this garden that reminded me of that other garden at home, on the top floor of a pagoda that couldn’t possibly pass for any pagodas I’d ever been to, as I stepped back from the edge of the sealed hole, our new reality began to settle inside me; ours, meaning my family’s, meaning the loss so recent there was no wound but only pain. We were caught in the instant between the attack of death and the appearance of traces it left on our bodies, and the pain was sudden, immense, and confusing, because we couldn’t see where we had been cut just yet. I stood there and looked out of the window at those trees below me, still and silent in the heat, and their silence seemed to attest to the beginning of a different structure of home, in the face of which there was nothing to be said. Our family was dispersed, living in multiple countries, and so was grief. So was the feeling that some of us had been away for too long, and now we would never be able to go back and find everything still the same. What happens when your understanding of home is invalidated, and in a sense it feels as if your home has failed you, because when you look back it is no longer there? Or it is there, but different. You remember how it used to be the same as you remember the face you have always seen in a mirror, and now it turns out to be a mirage. What is home but a mirage? Or, no, what is home but a mirage gone wrong, with too much reflection, too much light, too heavy a mass of heated air, tangled together like a malfunctioning smoke curtain? A smoke curtain conceals the location and movement of those inside it. What happens when it dissolves too fast, exposing everyone to the danger—but it is all expected, is it not, on a battlefield that will remain foreign no matter how close it is to home?—of never coming back, because you are outside that realm of relative safety now, and maybe you will feel betrayed, even, by this device that is supposed to protect you? On that particular day I felt rejected. I did, for we should have grieved together, not in different places, separated not by distance but because of our inability to talk about grief. My mother and I would keep circling around it, as if grief were an actual, physical midpoint we could locate in the middle of the ocean. There it was, a cold current flowing underneath all those waves, and no one else would know that it was made of our unspoken words, the invisible centre of every conversation. The location of grief was determined by measuring the distance between this garden and that and then dividing it by two: my reality, and a reality that was no longer. Together we also divided the weight of failure, and the garden was tainted by a death that shouldn’t have mattered for it at all, except now it couldn’t help but become at least a little haunted, carrying the weight from home that gave it the scent of home, faint, fermenting in the sun.

They attempted to build the pagoda in an authentic Chinese style, but they inevitably failed. Or were they trying, really? It was similar to designing a botanical garden so that it would mimic nature. But they knew from the beginning that it would never be nature. They could only hope that people would forget. If the garden was vast enough, the trees lush enough, every part of the foliage connected to one another as if they were one, a map showing all those green continents, then standing in the middle of it you might actually begin to forget. You might forget where you were, and more than that you might forget why, and how, it mattered. So what if it had been planned, planted, nature within city within nature? It was the act of forgetting that always brought representation one step closer to manifestation. Surely it would also be able to make a foreign land seem closer to home, or vice versa: forgetting, not remembering. They could also hope that people wouldn’t count how many floors the pagoda had, or that the number wouldn’t mean anything to the one who was counting. What if I forgot? What if I said, it didn’t matter in the end, because ten was as good as nice, this pagoda as good as any, the day as good as any to start spinning the thread of grief out of my body and burying it underneath a cypress tree as good as any, maybe a little tired, its needle leaves a little bleached by the sun? The day was so hot and I wished I could sit in the shade and find a fallen green needle lying there, waiting for me to pick it up. I wished I could take it to my skin and begin to understand the exact shape of a puncture wound, take it to my sweat-stained shirt and find that every loose thread fit its eye, and start to sew everything back to how it should be. But then, that would have been a fairy tale. I have been attempting to formulate this place into my home, but I inevitably fail. Or have I been trying, really? Maybe I’m just hoping to build something out of my failures, of seeing both gardens closing their gates in my face, of turning my face from those gates because they are both so clean yet so haunted, and I can’t afford to admit to that twice, in two places so far away from each other, as if it had happened twice, I mean the death of my grandfather, as if I had seen his trachea pierced open twice, twice there was blood, twice he stopped breathing. Through studying a mirror image you study the physical being you can’t bear to examine directly, and with a better understanding of the former you might just get closer to the latter. Here inside the pagoda I looked at it and saw my home, which was, and always had been, constructed on the basis of failure, and I saw that it would follow me anywhere.

For a place to become one’s home, one has to know where all the dead are buried. It can’t be a clean slate. In my home city all the cemeteries are set in remote districts, as far away from the central area as possible, and the one my grandfather is buried in is even farther away, because it is relatively new. I can’t say for sure the distance between the cemetery and my place, or my grandparents’ place, or that garden near their place. I don’t even remember how we might get to the cemetery from all these places, for every route involves multiple buses and subway lines and transfers. Maybe it is also in this way that the death of someone close to you estranges you from a place: it causes unexpected uncertainties. Not just regarding your half-day journey to the gravesite. That is the easiest one to overcome. Yet still, it will come as a surprise. How come there is the need to measure again, to locate again, to memorise again, when you used to believe that you were so familiar with your home you could find your way anywhere with your eyes closed? There arises the need to redefine yourself against the city, as if all of a sudden it no longer recognises you, and you become the only foreign word in the middle of a sentence in your mother tongue.

Still inside the pagoda there was a sign pointing to the directions of cities around the world, and one of them was Guangzhou. The sign noted its distance from London: 9,511 km. Reading all those different distances, one got the feeling that the city was treating itself as the heart of the whole world again. But this time I also thought of my mother, holding her box of egg tarts, boarding the train that would take her back home from Guangzhou, feeling sure of where she was going, not knowing it wouldn’t go as planned and there would be no way to make up for it because one’s first business trip would only ever happen once. I wondered if she knew how far she was from home. She was so young, I wasn’t born yet, and had she been told she would lose her father thirty-five years later she might not have thought much of it, it would have seemed so far in the future. After a few years a Hong Kong style bakery opened in Hangzhou and they could buy egg tarts without travelling somewhere else, but she would always say that it was not quite the same. Up until the death of my grandfather, my mother had not gone to Guangzhou again. I wasn’t expecting it but here I knew, I was confronted with the distance between me and the site of my mother’s primal mourning, over the death of a chance of sharing that would not come back. How strange that the number had been marked out, for me, by a pair of foreign hands. I wouldn’t have been able to be so precise, had I been back in our city, at the starting point of the journey that had led me here. How strange that this is part of what home is, for home is to know how far you need to travel, in order to grieve.